I think its important that people working in a particular field of expertise should be more than one dimensional and cultivate interests in other areas. I've always had a passion for history, literature and reading in general. A long time favourite book is Richard Holmes' "Footsteps", a book which combines biography, travel and autobiography. His biography of Shelley is also a favourite. So when I heard that a new book of his was due out that focused on the development of science in the "romantic age" I bought a copy hot off the press - even though it was in hardback, as I didn't want to wait the extra months it would take for a paperback edition to be published (mind you a half price offer made it even more tempting!).

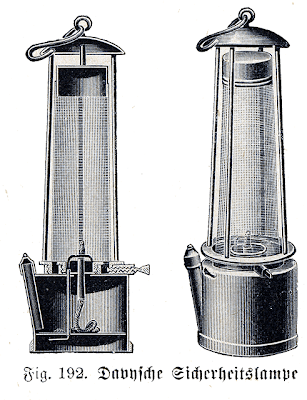

As in Footsteps, Holmes covers the life of more than one subject and also wanders off down sidetracks related to the main theme. One of the main topics is the life of Sir Humphrey Davy. I've always had an interest in this pioneering chemist so was keen to read this section of the book. He is best known for his invention of the safety lamp and he is also credited with the discovery (or isolation) of sodium, potassium and barium. But there is a lot more to his life.

Humphrey Davy came from humble beginnings in Cornwall, being born in Penzance in 1778. In 1794 he was apprenticed to John Bingham Borlase, a Penzance surgeon, but in 1798 was taken on to Thomas Bedooes to work as a laboratory assistant in the latter's newly established Pneumatic Institution in Bristol. It was here that Davy was able to develop his talents as an experimental scientist, before finally moving to London in 1801 to work at the Royal Institution.

There's a tendency these days to separate arts and science - but Davy moved in both worlds, as did many other prominent artists and scientists at the time. He was a friend of Wordsworth and Coleridge who took an interest in his work, as did others, including Shelley and Keats - Davy even wrote poetry himself. Men of ideas were interested in more than one sphere of knowledge and culture.

As an occupational hygienist it was particularly interesting to read about Davy's experiments with gases in Bristol. He explored the effects of nitrous oxide and carbon monoxide by conducting inhalation studies on himself. On more than one occasion he came close to death by exposing himself to high concentrations of carbon monoxide.

One of the things I admire about Davy was his invention of the miner's safety lamp. Although this is surrounded by controversy (not least disputes about who first developed the lamp with George Stevenson) Davy was largely motivated by a desire to save lives (although the search for glory was a factor too, it has to be said) and he refused to take out a patent, even though strongly encouraged to do so. He wanted his lamp to be freely available. Sadly, although the lamp was intended to save lives it has been said that it actually caused the death of more men because the mine owners used the lamp as an excuse to send their workers into more dangerous workings. However, the ones really responsible for this were the greedy mine owners. Davy cannot be blamed for the misuse of his invention by others.

Although he had radical tendencies in his youth, he moved to the right in older age as he became part of the establishment (sadly this is too often the case). He also had a tendency to seek glory and credit for inventions and could be jealous of others who worked with him - notably Michael Faraday who started out as Davy's assistant. Nevertheless there is much about him to admire and Holmes, who is clearly sympathetic towards his subject, has written an educative and entertaining account of his life. And although the book as a whole is excellent, it was worth shelling out for a hardback book for this alone.

No comments:

Post a Comment